Mission in Bubanza | from October 9th to 23rd, 2023

The five participants were: myself, Dr. Alfredo Antonucci, an anesthetist, Dr. Vittorio Podagrosi, a surgeon, and his kind spouse, Mrs. Rita el Mounayer, and Mrs. Francesca Pacini, formerly the head nurse of the Intensive Care Unit at San Gerardo Hospital in Civitavecchia.

The mission, following Dr. Piero Petricca’s foundation “Andare Oltre” unfolded constructively and purposefully.

There’s a pressing need to develop a therapeutic protocol for us doctors who, in various missions, find ourselves dealing with two of the most widespread, devastating conditions in the region: hematogenous osteomyelitis and skin ulcers.

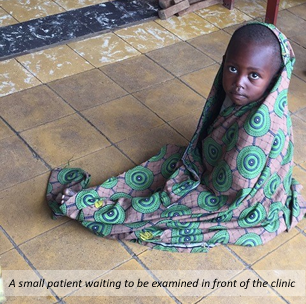

I share a brief account I hastily wrote upon my return, starting with the small protagonist, believing it speaks volumes about our motivations.

Pietro Ortensi

Jean Bosco

His name is Jean Bosco, like the saint founder of the Salesians and the Daughters of Mary Help of Christians, but for us, he is “the Kamikaze” due to the dressing on his forehead, which, with a certain imagination, resembles the “headband of commitment (hachimaki)” worn by Japanese pilots who launched themselves, without escape, against enemy ships.

His name is Jean Bosco, like the saint founder of the Salesians and the Daughters of Mary Help of Christians, but for us, he is “the Kamikaze” due to the dressing on his forehead, which, with a certain imagination, resembles the “headband of commitment (hachimaki)” worn by Japanese pilots who launched themselves, without escape, against enemy ships.

JB, the little warrior, delivered a strong blow that resulted in a small wound (three stitches of thin nylon), an inevitable side effect of his exuberant, uncontrollable, smiling vitality.

Friendly, affectionate (he often runs to hug us with sudden assaults), he is the opposite of those poor, small beings we are accustomed to seeing in their suffering, shamelessly and disrespectfully exposed, often for instrumental purposes.

Emaciated children with bellies swollen with ascitic fluid (like a cirrhotic adult), breathless from pneumonia, abandoned, crying, with runny noses.

Certainly, these are real images linked to poverty, war, and their dramatic consequences, but I find the monotonous use made of them wrong, to the point of creating, in those unfamiliar with that reality, the belief that African children are primarily or only those.

Near the Hospital of Bubanza in Burundi where we operate, there is a school attended by many very young students in light brown uniforms: a simple jacket and shorts.

From the corridor and the operating room, you can hear the energetic chant of the students memorizing (as was done in the past to learn multiplication tables: the basis of elementary mathematics).

One day, leaving the hospital just as classes ended and the students happily exited, finding myself among them, I had the questionable idea of giving some of them candies (always present in the lab coat pocket to “console” the little patients).

I had to run away to escape the joyful assault of cheerful, lively young people, similar (I believe) to their peers around the world.

Capable of playing with humble objects: an old, irrecoverable bicycle tire skillfully rolled with a stick, a ball made of rags rolled up to kick for an impromptu game. A small patient “kicked” alone, laughing at a balloon made by inflating a surgical glove.

Many of their peers here play with sophisticated, expensive electronic devices that they quickly tire of and lose interest in: something is not working.

Clearly, here we persist in seeking well-being and happiness, which all humans legitimately seek everywhere, in the wrong direction, which does not pay.

Humanitarian mission? Better to call it health collaboration. A phrase that defines our actions in a more balanced, real, and respectful way, with the intention of dissociating ourselves from any “colonialist” allusion.

We bring our baggage of knowledge and experience, which would otherwise be lost or scrapped (like a still valid car that can still cover many kilometers but no longer circulates due to new rules) for those of us who are retired.

We do our job, treating pathologies that are rare for us, sometimes only present in medical books. A different philosophy in action is necessary, having to deal with a reality where it is often difficult to follow patients for a long time and therefore directs us towards therapeutic choices, as much as possible, that are conclusive.

A true and challenging, daily and direct way for us doctors and nurses coming from such a different, changed reality.

His name is Jean Bosco, like the saint founder of the Salesians and the Daughters of Mary Help of Christians, but for us, he is “the Kamikaze” due to the dressing on his forehead, which, with a certain imagination, resembles the “headband of commitment (hachimaki)” worn by Japanese pilots who launched themselves, without escape, against enemy ships.

His name is Jean Bosco, like the saint founder of the Salesians and the Daughters of Mary Help of Christians, but for us, he is “the Kamikaze” due to the dressing on his forehead, which, with a certain imagination, resembles the “headband of commitment (hachimaki)” worn by Japanese pilots who launched themselves, without escape, against enemy ships.

Yet another fantastic experience in Burundi. While not easy and with a thousand difficulties, it was also full of joy and satisfaction! I shared this time with friends, Francesco, Achille, Stefano and Anna, a scrub nurse, whose enthusiasm, competence and humanity was a precious contribution. All happy and filled with what this land and its people give, but all too aware of the limits dictated by contingency and by the various local situations. There was not and certainly would not be, a manifestation of clear-cut orthopedic procedures. We all know that the reality we find is more like a war zone. We must consider the immense limitations an African hospital, which, regarding this facility, is at a good level. A really nice group, joined initially by Patrizia and Gianluca, was enthusiastically surrounded by a constant whirl of smiles, supported by the unforgettable messages of love from, above all, the children, the orphans, the patients and their families who repaid our work with expressions of gratitude that are priceless and that no one can ever take from our hearts. Thanks to all our “group” you were really great.

Yet another fantastic experience in Burundi. While not easy and with a thousand difficulties, it was also full of joy and satisfaction! I shared this time with friends, Francesco, Achille, Stefano and Anna, a scrub nurse, whose enthusiasm, competence and humanity was a precious contribution. All happy and filled with what this land and its people give, but all too aware of the limits dictated by contingency and by the various local situations. There was not and certainly would not be, a manifestation of clear-cut orthopedic procedures. We all know that the reality we find is more like a war zone. We must consider the immense limitations an African hospital, which, regarding this facility, is at a good level. A really nice group, joined initially by Patrizia and Gianluca, was enthusiastically surrounded by a constant whirl of smiles, supported by the unforgettable messages of love from, above all, the children, the orphans, the patients and their families who repaid our work with expressions of gratitude that are priceless and that no one can ever take from our hearts. Thanks to all our “group” you were really great.

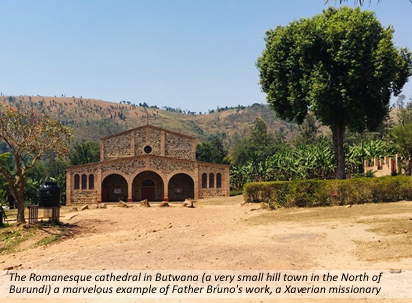

Christmas in Bubanza. We had the pleasure of experiencing the charm and magic of the most important Christian holiday at the Diocesan Hospital of Bubanza. The sung mass, celebrated at the cathedral, is one of the most important socialising occasions for all – mothers elegantly dressed, cheerful and festive children, the men dignified and composed – and us, who although certainly integrated, are always the object of a certain amused curiosity.

Christmas in Bubanza. We had the pleasure of experiencing the charm and magic of the most important Christian holiday at the Diocesan Hospital of Bubanza. The sung mass, celebrated at the cathedral, is one of the most important socialising occasions for all – mothers elegantly dressed, cheerful and festive children, the men dignified and composed – and us, who although certainly integrated, are always the object of a certain amused curiosity.